Food systems are defined as the web of activities associated with the production, processing, transport, and consumption of food - the system comprising interlinked sectors on land and in water. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) define sustainable food systems as those able to deliver food security and nutrition for all in a way that the economic, social, and environmental bases to generate such for future generations are not compromised.

Achieving sustainability faces several challenges across both food production and consumption which research will be essential to solve. An expanding global population which is increasingly urbanised, coupled with the growth in per capita income and shift toward Westernised diets are changing food demand and trade. Inequity in food systems leaves the poorest vulnerable to food insecurity. The small rural farmers, fishermen and herders who produce the majority of food globally struggle to access safe and nutritious food. As more must be produced with less (land, energy and especially water), minimising food losses and waste in existing supply chains has become a pressing challenge.

These challenges exist at a time when climate change and other anthropogenic forces (for example pollution) are altering the availability and suitability of land and water for growing food, and the interactions and feedbacks between food production, biodiversity and ecosystem services are better understood. In short, food systems must deliver human sustenance while becoming much more climate-efficient and supportive of the very biodiversity on which food production relies.

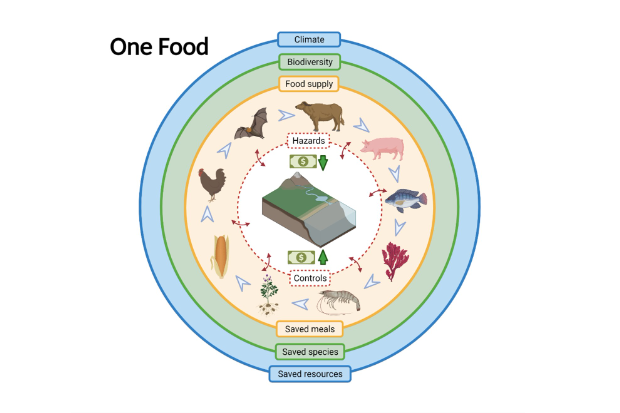

Globally, between 20 and 40% of food supply is destroyed by pests and disease. In recent years, Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) colleagues have argued that One Health principles (the recognition that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment -including ecosystems- are closely linked and inter-dependent) can and should be ‘designed in’ to aquatic food production. They have also demonstrated that hazards (whether chemical or biological) present within the environment are amongst the most significant drivers of supply inefficiency in the sector. By focusing on developing better policies to control hazards within food sectors, we assert that more, safer food can be produced– or, that the same amount of food (meals) may be produced with a smaller environmental footprint. Hazard identification and control then become a central tenet for better, safer aquatic foods that have less impact on biodiversity and climate.

If these principles work in aquatic food supply chains, theoretically they should be applicable to terrestrial settings – whether we are talking fungal pathogens limiting rice production or foot-and-mouth disease decimating cattle herds, these hazards not only have the potential to directly impact animal, plant, and human health, they also indirectly (and disproportionately) impact the local environment in which production takes place and the wider environment where these inefficient food systems exist. In summary, animal, and plant health are critical for human existence, diverse and plentiful hazards in food systems are major barriers to food security and poor hazard control underpins climate inefficiency and biodiversity loss.

The One Food project is proposing that new, holistic tools are needed to catalyse wide-reaching food-environment policy change. By working with economists, ecologists, climate scientists and social scientists from UK academia, and with government and academic partners in South Africa, we are looking to form a new ‘Community of Practice’ around these principles. Bringing previously disparate deep specialisms together around a shared focus – better, safer foods that have less impact on the environment – to calculate benefits of hazard control not only in terms of food and money, but also related to biodiversity and climate-efficiency per unit of food produced (Figure 1).

Identifying and controlling hazards (and the impact that they impart) at source may catalyse positive change which transcends traditionally discrete domains and should drive connection of policies which better link water, soil, and air quality with safer and more sustainable food supply. This rather obvious but nonetheless ambitious concept needs new conversations between colleagues who speak different technical and policy languages and who think at different scales and from different directions; it goes to the heart of how we value food and, those environments which make sustainable production possible.

Want to know more?

Find out more about One Health activities across Defra here.

Recent Comments