When I started studying my veterinary degree, I always envisaged that I would return to Yorkshire to work in mixed practice (think James Herriot!). It was in my third year of university teaching that I became fascinated by zoonotic diseases (diseases that can be transmitted from animal to humans and/or from humans to animals) and the critical role that veterinarians can play in a One Health approach to control them.

One Health is an integrated, collaborative approach to optimising the health of humans, animals, and the environment, and involves transdisciplinary, multisectoral working across society. It was this interest that led me to undertake an MSc in One Health after graduation and subsequently join APHA as a veterinary inspector, before moving to the bacteriology team at APHA’s headquarters near Weybridge.

The team I sit in works as part of a multidisciplinary team focusing on the control of and research into Salmonella. Salmonella is a type of bacteria which can be found in animals, and human infection can cause gastrointestinal illness. I also work on a variety of other zoonotic pathogens such as, Shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC), Corynebacterium ulcerans and Cryptosporidium, which forms the subject of this blog.

I thoroughly enjoy being able to apply my veterinary knowledge and skills to make a difference to animal and human health and welfare through working on zoonoses.

One of the most challenging, but interesting, parts of my job is working with colleagues during outbreaks of zoonotic diseases, when we adopt a One Health approach, working across agencies and disciplines to implement measures and actions to control the outbreak. Cryptosporidium outbreaks are a good example of APHA’s work on zoonotic disease outbreaks.

Cryptosporidium is a type of gastrointestinal parasite. On average over 4000 human cases of diagnosed Cryptosporidium illness (“cryptosporidiosis”) are reported in England and Wales annually, although case numbers may be greater as infections may go undiagnosed, for example if an individual does not seek medical attention. Cryptosporidiosis is most common in children aged between one to five years old. In people, it can cause a variety of symptoms, the most frequent of which is acute watery diarrhoea. People with weakened immune systems, such as those on some immunosuppressive drugs or with inherited conditions, untreated HIV/AIDS, or malnourished children, are at greater risk of serious illness.

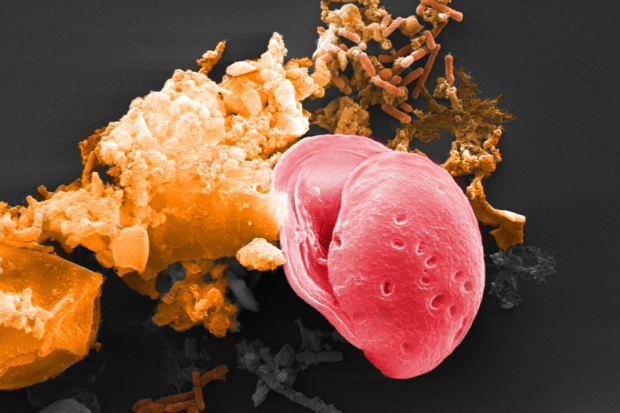

There are many species of Cryptosporidium. Most human infections in the UK are caused by either C. hominis or C. parvum. C. hominis is typically transmitted from person to person. C. parvum is the most important species from a zoonotic perspective, as it lacks host specificity so can infect many animal species and humans. Infection is via the faecal-oral route, that is humans ingest the oocysts (the transmissible stage of Cryptosporidium shed in faeces from an infected person/animal) and become infected. Humans can become infected through a variety of routes such as via contaminated water or through direct contact (for example petting) or indirect contact (for example through contact with animal faeces) with infected animals.

Cryptosporidiosis is an important disease of animals too, especially for young ruminants where infection can cause outbreaks of diarrhoea. Infected animals may show no signs of disease and can shed high numbers of oocysts. These oocysts are directly infective, resistant to disinfection and can persist in the environment for long periods of time, especially in cool, moist conditions.

In England, laboratory identification of Cryptosporidium in humans must be notified to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) by the diagnostic laboratory. This means that the UKHSA has surveillance data to enable their scientists to monitor trends and investigate where there is an increase in cases, which at a local level may indicate an outbreak is occurring. During outbreak investigations, information is gathered from human cases on common exposures and risk factors, such as recent contact with animals or travel, which helps in identifying possible sources of infection. Similar processes are in place in the devolved nations.

APHA is requested by local Health Protection Teams to assist when a human Cryptosporidium outbreak is thought to be linked to animal contact.

A Cryptosporidium outbreak is usually identified by public health professionals following an increase in the number of human infections, exceeding the expected number of cases for the population and time period, or when cases have a common exposure such as a venue or food product, or when numerous individuals are infected with a genetically identical type of Cryptosporidium. Once a Cryptosporidium outbreak is identified, UKHSA convenes an Incident Management Team (IMT) that meets to discuss the outbreak, investigations required and control measures. The IMT consists of individuals from a range of disciplines and agencies such as Local Authorities, NHS, Food Standards Agency, Environment Agency, Health and Safety Executive and include communication specialists, epidemiologists, and microbiologists who each bring their own specific knowledge and skillset. APHA veterinarians attend to specifically advise where there are thought to be animal aspects to the outbreak.

If required, APHA will visit livestock premises linked to Cryptosporidium outbreaks. Specially trained APHA veterinarians visit the site and provide advice on measures to reduce the risk of transmission of Cryptosporidium and other zoonotic organisms and how to improve compliance with the code of practice for animal contact at visitor attractions, if applicable. These visits may be undertaken by Environmental Health Officers from the Local Authority. Animal samples (poo picking!) may also be collected at these visits and sent for testing at one of APHA’s laboratories.

Early sampling of animals in Cryptosporidium outbreaks is critical to increase chances of detection so we must move quickly once an animal source is suspected. APHA veterinarians will also liaise with the private veterinary surgeon (PVS) for the premises – working with the PVS in outbreaks such as this is very important and highlights the need for continued collaboration between PVSs and APHA.

Any animal samples from which Cryptosporidium is detected at the APHA laboratory are then sent to the National Cryptosporidium Reference Unit, which is managed by Public Health Wales in Swansea, for further characterisation. Further analysis can be undertaken, for example comparing the of the animal and human isolates to see if there is a match. Work is continually ongoing to improve the sensitivity of detection of Cryptosporidium in animal faeces.

The IMT will meet throughout the outbreak to discuss recent developments, findings and progress. Once the outbreak is declared to be over, the work does not stop – next comes the creation of an outbreak report and, importantly, discussions of lessons learnt from the outbreak, so IMT members can continually improve and develop their approaches. Variations of this approach are employed for a variety of different types of disease outbreaks.

I hope this has given a glimpse into some of APHA’s zoonotic disease work and how we operationalise the One Health approach during outbreaks. Addressing such issues requires transdisciplinary team working and it is a privilege and a pleasure to be able to work with and learn from talented colleagues within APHA and beyond!

3 comments

Comment by Linda Smith posted on

I'm so glad that you're enjoying work and contributing to a very interesting work area.

I recall a crypto outbreak in school children several years ago. The open farm only offered hand sanitiser after touching the animals, instead of hot water and soap. Cryptosporidium is not affected by hand gel, and many small children became infected.

Comment by Lisa Peddle posted on

Thank you for sharing this post. It is very interesting, we studied One Health as part of our undergraduate studies but it is interesting to read about it in context. I am doing an MRes at Nottingham University on calf health and Enteric disorders, and crypto is one of the most significant conditions leading to calf mortality. Thanks for sharing.

Comment by Cameron Stewart posted on

Excellent summary of Crypto from the One Health perspective.

Great electron micrograph of a Cryptosporidium oocyst!