Our next instalment in our celebrating votes for women series explores the career highs and lows of one of the UK’s first female veterinarians to graduate in the early ‘30s.

A pioneer in many ways, Connie Ford’s ground-breaking research on fertility/infertility in cattle at our Veterinary Investigation Centre in Sutton Bonington spanned across three decades and gained her an MBE. However, you’d be misguided to think that this is all there is to Connie’s life..

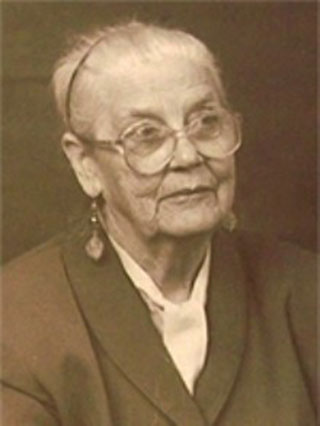

Connie Ford MBE

Connie Ford MBE: veterinarian, poet, political activist and serial documentalist (1912-1998)

Early life

Connie Mae Ford was born in east London in 1912. Despite feeling a ‘vague medical leaning’, she first contemplated secretarial training as a young girl, failing to make the connection between ‘watching live things in a field [which she thoroughly enjoyed, especially birds] and dissecting dead ones in the laboratory’.

It was her science mistress, who had heard Professor Sir Frederick Hobday, Principal of the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) in London, speak on veterinary surgery as a new career for women in 1927, who (thankfully for APHA) convinced Connie to train as a veterinarian. She was given a three year scholarship for the RVC, provided her father could pay for the fourth (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/9).

Vet school & looking for work

Connie was one of the first 30 women to graduate from the RVC in 1933, six years after the college was first open to women. Aleen Cust was the first woman to be awarded a diploma of membership in 1922 by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) more than two decades after she was denied the opportunity to join on account of her gender.

On this, Connie wrote: "To the women students, only admitted to the London Veterinary College in 1927, (Dr. Cust) was a legend and an example, her name a private battle cry in their darkest moments. If they got on so much better than the old men of the RCVS had predicted, it was the trail blazing of this remarkable woman that eased their path" (Extract from https://www.avma.org/News/JAVMANews/Pages/110601v.aspx)

Interestingly, Connie openly rejected the Society of Women Veterinary Surgeons (1941-1990) fearing that it would lead to greater segregation from the main body of the profession. Later, in 1966, she was elected President of the East Midlands Branch of the British Veterinary Association.

In her essay “Professional Entrepreneurs: Women Veterinary Surgeons as Small Business Owners in Interwar Britain”, Julie Hipperson, who sieved through Connie’s paperwork in great detail, wrote: “Connie’s jubilation at becoming MRCVS quickly turned to despondency. She […] found it difficult to secure ‘seeing practice’, she had neither personal contacts nor the accumulated experience to persuade employers that, despite her sex, she would be a competent assistant. Applications to advertised posts went unanswered, promising personal leads came to nought, and […] the general consensus amongst her friends was that senior male vets were ‘all afraid to have a woman!’” (Social History of Medicine (2017) Vol. 31, No. 1 pp. 122–139).

Setting up practice

Like many of her female MRCVS peers, Connie quickly came to the realisation that putting up her own plates, and opening a practice in her parents’ front room, might be her only chance to practise. Feeling it was ‘better to be in debt than to lose what skill I have through lack of practice’, she approached the Connolly Memorial Fund, a charitable organisation which normally granted training loans to women to become teachers, but granted Connie a loan of £100, payable in instalments.

Julie Hipperson wrote: “A costing made by Connie for her application shows that the costs [of setting up practice] could be prohibitive - even during an era in which a basic surgery with rudimentary fittings and equipment were deemed sufficient to practise small animal medicine. In a period when domiciliary visits were the norm, Connie’s greatest expenditure was the purchase and taxing of a car (£20), [and] the building of a garage […] (£14).”

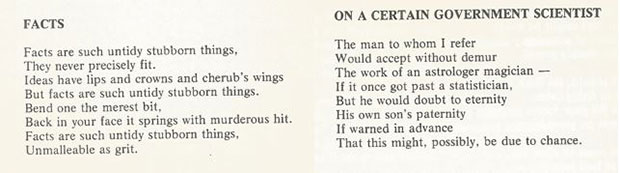

With the traditional mixed general practice still very much considered a male’s domain, women vets were often relegated to caring for pets, a state of affairs Connie (who in private was very vocal about her dislike of dogs) was very unhappy with.

Her scientific curiosity was piqued though when working with one of her clients, a retired cabaret dancer, who had amassed a private menagerie of over 80 monkeys. “So far as I know, I am the only person in England to whelp one [a capuchin]. It’s nice to have done something unique if only whelping capuchins”. (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/6 and 3/3).

Early women vets like Connie were primarily from a middle-class or upper middle-class background and had very little direct experience of financial affairs. Connie lamented her lack of exposure to the business side of practice (as an assistant) for her ‘gross inefficiency’ in book-keeping and organisation, which in turn had lowered her profit.

After seven years in practice, her net income was still only £160, which she felt was little to show for her hard work. “Of course I am not wealthy but there were times when I despaired at even being solvent" (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/6).

As work for private practitioners dried off during the war, with fewer people being able to afford to pay a vet’s fee, Connie found herself with less and less work and in 1941 she started volunteering every day from 6am to noon at her local Air Raid Precautions first aid post. She was becoming increasingly frustrated with not being able to do the veterinary work she trained for and longed to leave the world of dogs, cats and exotic pets behind.

In her characteristic 'say it as it is' style, she wrote: “Private practitioners - for all the backscratching [undecipherable word] at NVMA [National Veterinary Medical Association] branches meetings - are no longer the backbone of the profession. They are unfortunate people forced by lack of other means of support to prostitute their intellect and powers for the delight of the highest bidders, while other valuable work they could do […] goes undone. The people who do the important work now are to my mind the research workers, veterinary inspectors, advisory officers and special investigation men. These are the [undecipherable word] of an efficient nation-wide system which, if and when the economic structure of the country is changed, will blossom and bear fruits in the tenfold health and productivity of our farm stock.” (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/6).

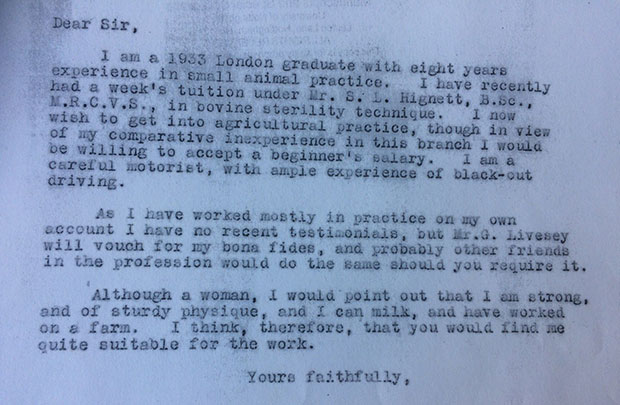

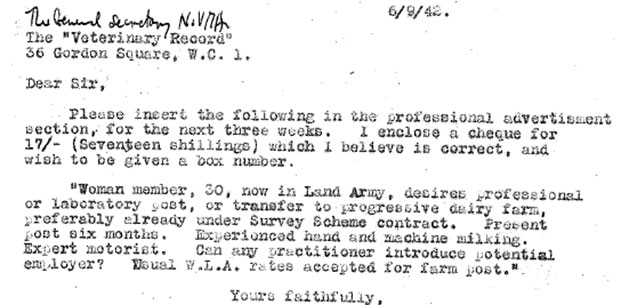

She dedicated a lot of her time applying for various positions, stating that despite her eight years in practice she would be willing to accept a beginner’s salary for any chance to work with cattle and gain agricultural practice.

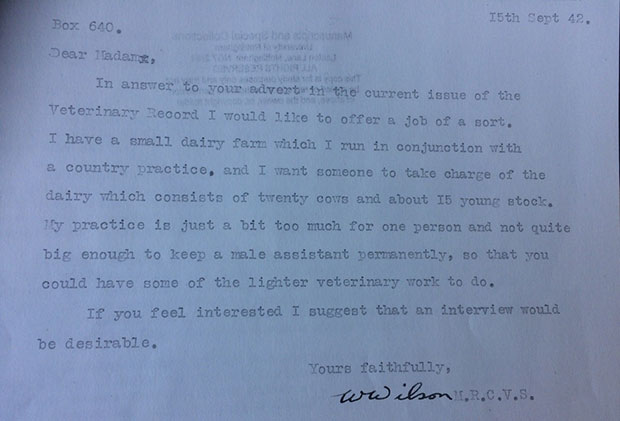

Some of the answers she received convey the attitudes towards female veterinarians of the time.

Sutton Bonington

In 1943, following a one year stint in the Scottish Land Army, Ford was finally offered a temporary war time appointment as assistant veterinary investigation officer at the Midland Agricultural College (now University of Nottingham), moving on to Harper Adams in 1943 (leaving following a row over salary!) before joining Liverpool University in June 1944 (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/2).

The Veterinary Investigation Laboratories were incorporated into the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food in 1947, the year when Connie officially became a civil servant.

She then worked, until she retired in 1972, for the UK Government's Veterinary Investigation Service at Sutton Bonington, finally able to dedicate her work on fertility/infertility in cattle: a topic she had been passionate about throughout her years studying at RVC.

A poet

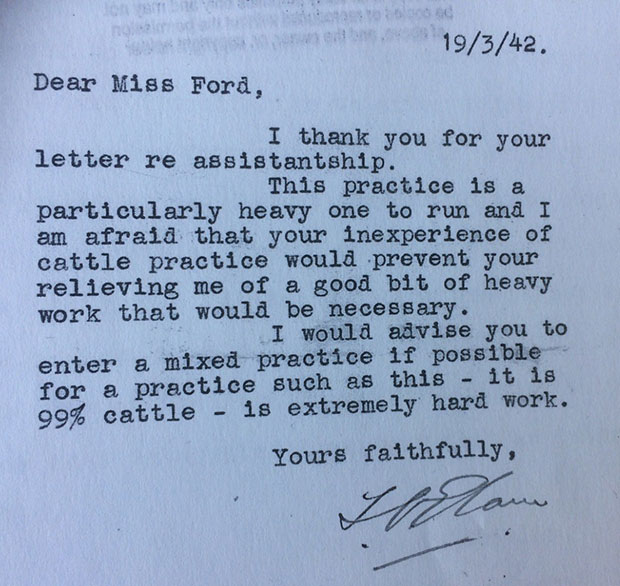

Connie had written poetry throughout her life (she wrote her first poem aged six) but, in the 50s, she became an active member of the Nottingham Poetry Society and began to submit her work to competitions and writers' groups.

Quite unusually for a poet, Connie wrote comprehensively on every aspect of her life. Her work appeared in various poetry magazines and publications including the annual poetry workshop magazines of the Society of Civil Service Authors.

Her poem 'The Great Eastern', based on her grandfather's journal, won the John Masefield Prize in 1968. Connie published four books of her own poetry: 'Veterinary Ballads and Other Poems' (1973), 'Wings and Water' (1973), 'Boat Crazy' (1975) (Connie was a very keen sailor), and 'The Crimson Wing' (1977). I thoroughly recommend perusing the former, as many of her poems will still strike a chord with those of us working at APHA today.

Recognition

Connie Ford was awarded an MBE in 1970 for her lifelong work on advancing the understanding of abortions and infertility in cattle.

After retiring Connie spent seven years writing the biography of Aleen Cust, Britain’s first woman vet, which she self-published in 1990 (Biopress, Bristol) after receiving 41 rejections from commercial publishers (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/15).

In 1992, she received the J.T. Edwards Memorial medal presented in recognition of her “indefatigable work writing up Aleen Cust biography.” (Veterinary Record 15/8/1992)

Politics

As vocal about her political ideas as she was about anything else, Connie was a lifelong member of the British Soviet Friendship Society and supporter of women's rights, often speaking at local women’s group events.

In a letter to a male friend in 1939, she writes: “Probably by now you think that I am a hopeless idealist or worse still a dangerous revolutionary. Maybe so, I can’t help what others think of me.” She was very happy to recollect that she had “lived to see over quarter of the veterinary profession, and half of the veterinary students being women” (Manuscripts and Special Collections, the University of Nottingham, from CF 4/2/9).

Legacy

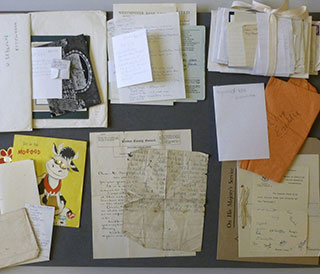

Connie died in 1998. A friend recalls: “After her death, the mammoth task of clearing out her flat was full of surprises. The boat on her balcony housed pigeons sitting on eggs. Drawers and cupboards contained a compressed history of Connie’s life.” (In Walking my Tightrope by Cathy Grindrod, Nottingham: Poetry Nottingham Publications, 2001).

The thousands of papers Connie left behind are held by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (archives with a focus on her professional life) and Nottingham University (archives with a focus on her literary life). (In Walking my Tightrope by Cathy Grindrod (Nottingham: Poetry Nottingham Publications, 2001)

Connie left a generous bequest to The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons Trust, which offers Connie Ford Retraining Grants for the development and delivery of retraining courses for UK veterinary surgeons.

Acknowledgements

Cathy Grindrod, Dick Lane, Zoe Ellis (Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham), Lorna Cahill and Helena Clarkson (RCVS Knowledge).

Follow APHA on Twitter and don't forget to sign up to email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by Julie Lane posted on

fantastic and thought -inspiring article

Comment by Charles Lane posted on

My dad Dick Lane met Connie Ford many years ago and she was an inspiring person and a pioneer for women as Veterinary surgeons, great article and thanks for bringing this fascinating story to light