One Health Day highlights the need for a collective approach to tackling joint disease threats to people, animals and the environment. It is celebrated annually, with the sixth event happening on November 3.

In 2019, the APHA Science Director wrote a blog explaining how One Health is integral to APHA science. This blog highlighted APHA’s national and international collaborative work across all of our science portfolios to detect and control a wide range of diseases, including zoonotic diseases which can be transmitted from animals to humans.

This year, we hear from Dr John McGiven, APHA Disease Consultant for brucellosis, as he talks about APHA’s role in recent cases of Brucella canis in Great Britain (GB) and how we immediately pulled together with the UK Health Security Agency (formerly Public Health England) to respond to this new threat.

Report of Brucella canis in imported dog

In June 2020 I received an email from my APHA colleagues in the Surveillance and Laboratory Services Department (SLSD) about a positive Brucella canis blood test result, the scale of which I had never seen before. I checked the submission form and saw that it described an imported dog that had recently aborted. There have previously been less than a handful of confirmed cases of B. canis in GB, but this looked like the real deal and rang alarm bells.

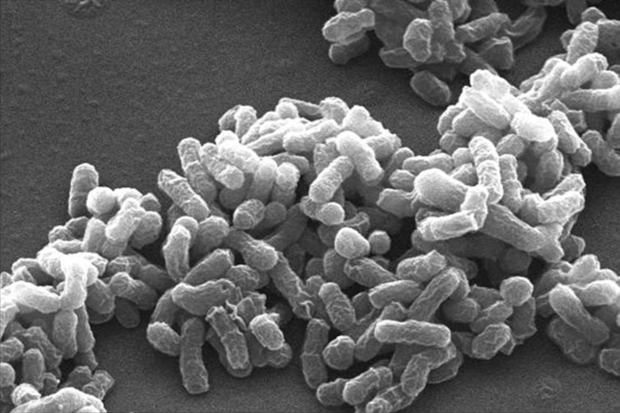

B. canis is a zoonotic bacterium (meaning that it can cause disease in humans) and is listed with other Brucella species as a biohazard category 3 human pathogen. Abortion material from infected animals contains very high numbers of infectious B. canis cells and contact with this is one of the main ways in which both dogs and humans can acquire infection. So, there was ample scope for concern.

The preferred host of B. canis is dogs and it causes the disease canine brucellosis. Other species of Brucella also have preferred hosts, including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, seals and whales, although most can also infect people. The Brucella species we have historically been most concerned about are those infecting livestock due to the production losses that result and the threat to public health.

Globally it is estimated that between three million and 12.5 million people a year contract brucellosis from animals, almost exclusively livestock. GB is free from brucellosis in livestock and wildlife and, until recently, it was also not found in dogs.

As with other animals (but not humans) the disease in dogs causes abortions although some pregnancies can be successful. Infected dogs also frequently acquire other clinical signs - most often chronic and debilitating back and rear limb pain. However, some may appear visibly well yet can still be infectious and may go on to develop disease. Unfortunately, unlike in humans, the disease is not considered curable in dogs.

Working together

Upon viewing that report in June, I immediately contacted the APHA One Health Team. They engage in cases with potential zoonotic ramifications and regularly interact with a network of contacts working in public health. They, without delay, informed the Zoonoses team at Public Health England (PHE), now the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), as the case occurred in England. PHE engaged their colleagues from the local Health Protection Team (HPT) and clinicians with specialist knowledge of human brucellosis from the Brucella Reference Unit based at Liverpool University Hospitals.

We rapidly met to discuss the case at hand – the first of many virtual conference calls on B. canis over the coming months as multiple further cases emerged. I was also invited to present information at the meetings of the Human Animal Infections and Risk Surveillance (HAIRS) group, the government One Health operational risk assessment group.

Our priority was to help PHE identify people who may be at risk of infection and to limit the spread of B. canis. Together we identified scenarios we considered to constitute high, medium, low and negligible risk of infection from dog to human and from dog to dog.

As human-to-human infection is thought to be extremely unlikely, understanding dog-to-dog transmission pathways, including the role of environmental contamination, was critical to not only safeguarding animal health, but also human health. These judgements could only be made with the pooled knowledge of the assembled multi-agency team of veterinarians, clinicians, epidemiologists, bacteriologists and disease specialists.

We also determined actions to go alongside each assessment of risk and how, and who, was going to follow those up. It was evident that this too could only be achieved by the veterinary and human health partners working together.

Practical examples of this included the tracing and testing of potentially infected people and dogs. This was a feedback process that relied on the public health epidemiologists from PHE, the local HPTs, the laboratory at APHA where most of the testing was done, and expert interpretation by the medical and veterinary specialists.

We also spoke to our European colleagues, many of whom have a similar disease situation. This helped ensure we were aware of any useful information that could help us to improve our approach.

The GB multi-agency team also worked together on communication with affected people and to the broader veterinary and laboratory community to raise awareness of this disease from a very low base.

Examples include:

- the Chief Veterinary Officer’s letter to the Veterinary Record

- the APHA canis summary information sheet

- HAIRS Risk Statement on canis.

This latter document identifies the challenges presented by B. canis and is well worth reading. It highlights a significant number of knowledge gaps, some of which are critical to close before we can get the better of this disease.

I am pleased to say that we have been able to narrow some of these through the hard work of our above-mentioned colleagues in public health (in England, Scotland and Wales) and the teams at APHA (not just the Brucella Reference Laboratory that I work in but also the team in SLSD, the One Health Team and the regional laboratories). This includes better tools for detection, a better understanding of disease transmission and the virulence of B. canis for humans.

The new tools and knowledge enable us to refine our approach to control and provides valuable information to policy colleagues. We have also worked closely with policy colleagues in Defra and the Devolved Administrations and cleared communications lines with them.

Continued collaboration is critical

On a personal level, I have been struck by the commitment of all of the teams described above especially those individuals continuing their lab and field work throughout lockdown. The appetite of the public health bodies to take on B. canis in such a thorough manner at a time when they have been stretched like never before has been incredible.

Yet I also acknowledge that despite the big efforts and best intentions not every plan or action has run smoothly each time. I also know that for dog owners many difficult and sad situations have occurred, and very difficult decisions made. I am a dog owner myself and would abhor finding myself in these positions.

Cases of canine brucellosis continue to occur but as yet are all still associated with importations. I believe there is still time to prevent the disease from taking hold. The continued co-ordination of a One Health response will be critical as will be continued communication to raise awareness of this disease amongst owners, breeders, importers, rescue and rehoming charities and veterinarians.

“As the UK’s Deputy Chief Vet I am all too aware of the distress that can be caused by animal diseases such as brucellosis. Not just to the health and welfare of the animals they affect, but also to the livelihoods and well-being of those who depend on them, and crucially, the risk of zoonotic infections passing to people from the animals affected.

I commend the work of APHA, DEFRA, UKHSA and other colleagues who, when the alarm bells do ring, already rapidly employ these critical One Health approaches. Collaboration with our public health colleagues, and in fact wider, is essential for the effective mitigation and prevention of wide-ranging threats - and I am incredibly proud of our ability to do this so effectively.

The need to work in such a holistic way will only grow as the interconnections between humans, animals, plants and the environment become increasingly complicated. I fully support Defra group and cross-government efforts to build on this and raise awareness of the value of One Health in achieving the best outcomes for us all.”

Dr Richard Irvine, Deputy Chief Veterinary Officer, Defra

Find out more

- One Health blog catalogue

- Dr John McGiven’s biography.

- Canine Brucellosis: Summary Information Sheet

- Buying Pets Safely campaign

- Government Vets One Health Day blog

Recent Comments