Please note, this blog contains images of infected animals which some readers may find distressing.

The National Emergency Epidemiology Group (NEEG) is a multi-disciplinary APHA Cross Directorate emergency group which is rapidly formed in response to disease incidents with high potential impact for animal or public health, and/or rapid spread.

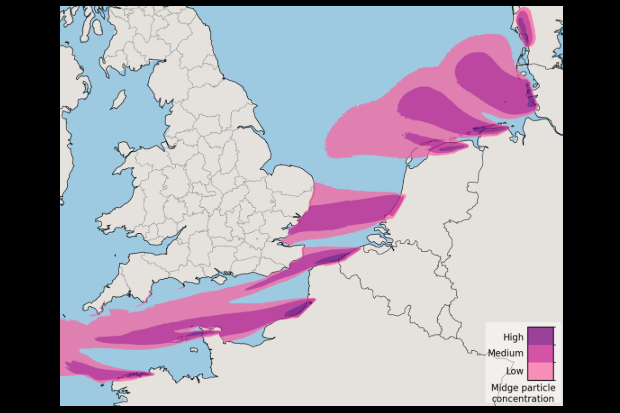

The NEEG has a team of epidemiologists who do desk-based work to monitor for potential incursions of exotic animal related threats to Great Britain (GB) via routine surveillance programmes in our national livestock populations. An example is an annual survey run in counties along the south and south-east coast of England to monitor for potential incursions of the bluetongue virus from the nearby Continent. The survey is designed by APHA’s analytical epidemiologists and scientists in collaboration with virus experts at The Pirbright Institute, informed by bluetongue outbreaks in Europe and modelling by the Met Office of the potential destinations of midges blown from the Continent into GB.

Bluetongue is a vector-borne viral disease affecting wild and domestic ruminants (for example sheep, cattle, goats, deer) and camelids (for example camels, llamas, alpacas). Bluetongue disease is an exotic notifiable disease in GB, meaning that, if suspected, it must be reported to the appropriate authority (APHA). It does not cause infection in humans. The bluetongue virus (BTV) is spread primarily by midges (small biting insects, a few millimetres long) that become infected by feeding on animals that have the virus circulating in their blood. Although more rarely, it can also spread from pregnant animals to their unborn offspring and through biological products (for example blood or semen).

Because of its transmission mainly via midges, the disease is seasonal. There is a low-risk period during winter, when midges are inactive or dormant, and a higher risk period from spring to autumn.

Bluetongue is important as it can cause animal disease, threaten animal welfare, reduce productivity as well as result in loss of trade with significant economic consequences. That is why it is essential, if the disease arrives, we tackle it at APHA working together with Defra and the Devolved Administrations in Scotland and Wales, the livestock industry, The Pirbright Institute and other colleagues, as quickly as possible, so that our national herds are protected, and industries continue to thrive.

The previous incursion of BTV in GB was due to a type of the virus, called BTV serotype 8 (BTV-8) in 2007, with several affected farms. That outbreak originated from infected midges blown over from the near continent and was eventually controlled by vaccination.

The annual survey for BTV has been implemented in counties along the south and south-east coast of England for several years with no detected incursions but that was due to change when, early in November 2023, the NEEG epidemiologists were notified by our testing lab at The Pirbright Institute of a positive result in a cow sampled as part of the annual survey. That was of a type of the bluetongue virus, called BTV-3 for which there is no vaccine available.

Several cases of BTV-3 have been reported in northern Europe since September 2023, mainly in the Netherlands but also in Germany and Belgium.

Following detection of the first case of BTV-3 in GB on 10 November 2023, the UK Chief Veterinary Officer, Christine Middlemiss, declared a 10km Temporary Protection Zone (TCZ) in Kent which limited the movement of livestock to control spread of the disease. Further work of NEEG analytical epidemiologists led to the development of a surveillance strategy to check if the bluetongue virus was circulating between our livestock and midges and to determine the extent of the infection. Further sampling by the annual survey identified another positive result in a cow in Norfolk, which led to an additional TCZ declared in Norfolk on 8 December. Both zones were lifted on 19 February 2024.

“Today, as Bluetongue is on our doorstep, the work APHA colleagues do is an integral part of our scanning surveillance strategy which helps us to define the hazards occurrence, enhance our contingency plan preparedness and mitigate animal health risks. It is vital therefore to maintain the integrity of UK Surveillance system which includes our Horizon Scanning Surveillance as well as our Risk-based Targeted and Active surveillance activities undertaken by veterinarians, scientists and livestock keepers.”

UK Chief Veterinary Officer, Christine Middlemiss

By 19 March 2024, 126 individual animal cases infected with BTV-3 had been identified in four counties in England as the result of TCZ surveillance activities and tracing investigations to prevent spread of disease via the movement of infected animals. NEEG field epidemiologists developed a risk assessment tool to inform actions taken on traced premises, according to the risk for spread of the disease.

To date, no clinical signs of disease have been observed in infected animals, which were all detected by blood tests. As no signs of disease have been seen so far in GB, it was even more important to ensure that awareness of the disease was raised among the farming community. That was achieved via communications distributed to farmers in the affected areas, as well as via major industry stakeholders, including veterinary organisations.

Epidemiologists and scientists in the NEEG will continue to investigate and report on any new cases of BTV-3 being identified in the future.

More information about bluetongue virus is available on GOV.UK.

------------------

This blog was authored by the National Emergency Epidemiology Group, with contributions from colleagues inside and outside APHA, notably the Veterinary Exotic Notifiable Diseases Unit, the Surveillance Intelligence Unit, the Outbreak Central Services team, the Met Office, and The Pirbright Institute.

Recent Comments