How APHA epidemiological modellers are using the Cloud to build more flexible analyses on disease transmission and control.

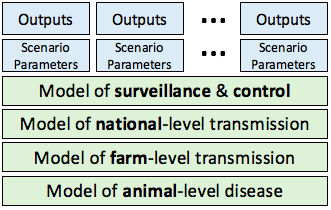

Computer models can help inform disease control policy by simulating transmission across livestock populations and then predicting the impact of potential control measures.

Key challenges include accurately modelling disease pathways and spread rates so they reflect reality, but models

Key challenges include accurately modelling disease pathways and spread rates so they reflect reality, but models

should also be flexible to a range of potential policy questions, which may change faster than new models can be developed.

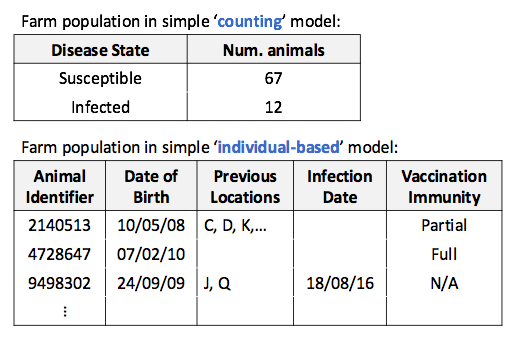

When thinking about how to build a flexible model for disease transmission between farms, we consider issues such as how animal populations should be represented in the program code. At the simple end of the spectrum we could keep count of the number of animals in different infection states – let’s call this the ‘counting' approach. At the other extreme, we could track each individual animal across its lifetime, recording its disease status, movements, age, and testing history – let’s call this the ‘individual-based’ approach.

The ‘best’ method varies along this spectrum but the individual-based approach, being a closer representation of reality, is more adaptable to unexpected policy questions. For example, questions around the predicted impact of additional testing based on animal history would be better addressed by an individual-based model which directly deals with history.

Building an individual-based model is challenging and APHA is part of a collaboration led by the University of Glasgow to develop an individual-based cattle disease transmission model of exceptional detail. The model tracks around 9 million animals per year and requires the memory equivalent to three desktop PCs, taking about one minute to run each year of simulated disease transmission. In the last six months we’ve undertaken several model fine-tuning activities, involving running the model millions of times, which would have taken around 50 years on a single computer.

To address the runtime issue we rented thousands of processors in the Cloud, but procurement was a challenge. Most pay-as-you-go Cloud services require invoices in foreign currencies and require contracts and/or credit cards, but the Civil Service favours fixed price contracts in Pound Sterling. Fixed price contracts are fine when IT needs are predictable, such as when running email servers for an organisation, but scientists’ requirements change quickly depending on what gets commissioned and discovered.

Furthermore, there is understandable reluctance to give scientists the ability to incur unexpectedly large bills at the end of the month. Our solution was to work with Strategic Blue, a financial cloud brokerage service, to develop a new kind of IT service contract in which some overspend risk is transferred from us to them, we receive deal terms that better suit our procurement needs, and we can switch cloud suppliers at a moment’s notice.

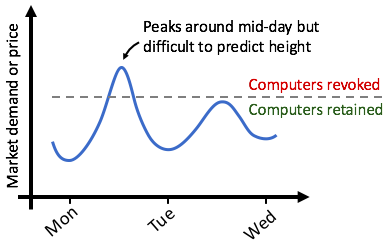

Cloud isn’t necessarily cheap, but we found some suppliers offer heavy discounts, often more than 75% off, provided you’re willing to have the computers taken away at short notice when the premium paying customers need them. So by writing algorithms which can cope with having the ‘plug pulled’ when market demand fluctuates we’ve been able to access many more computers within the same budget.

Cloud isn’t necessarily cheap, but we found some suppliers offer heavy discounts, often more than 75% off, provided you’re willing to have the computers taken away at short notice when the premium paying customers need them. So by writing algorithms which can cope with having the ‘plug pulled’ when market demand fluctuates we’ve been able to access many more computers within the same budget.

Making the technical details work has involved writing smarter code, learning to secure IT networks, automating computer setup, and cost monitoring. Thankfully, academia and industry have been doing this for a long time so the software tools and support are ready. It’s taken a year to get everything running smoothly, and has highlighted that modellers today need strong expertise in scientific computing to exploit new technologies and push research methods forward.

Follow APHA on Twitter and don't forget to sign up to email alerts.

Recent Comments