Veterinary Epidemiologist, Phil Jones, works in APHA’s Surveillance Intelligence Unit and talks about how APHA is looking to exploit new data sources to support its scanning surveillance activities to look for new animal disease threats.

It is often said that society’s ability to generate data far exceeds its ability to do anything useful with it.

Real life example

Just think of the amount of data you will generate in your life through social media, free Wi-Fi connections and the next time you shop online. For example, data about the products you buy, such as nappies and back-to-school items, can say a lot about you and your household, such as suggesting a new arrival or school-aged children. These inferences may not be correct but it’s not surprising that supermarkets spend a lot of time and effort defining customer profiles from purchasing behaviour in order to target their ‘special offers’ more effectively.

How is this relevant to animal health?

There is little doubt that animal health is intimately linked to human health; from rinderpest epidemics in cattle during the time of the industrial revolution to bovine tuberculosis in milk and the more recent examples of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), Salmonella in eggs and Campylobacter in chickens. It is clear that diseases in animals directly impact the health of associated human populations in a variety of ways including zoonotic diseases (namely those that can pass between animals and humans), the supply of safe and sufficient food, and the financial and economic impacts on those who depend on the agriculture industry.

The need to monitor diseases in animal populations is of critical importance for government and the livestock industry. But what is the most effective way to ‘surveil’ animal diseases? It is not a straight-forward question, especially as we often don’t know what we’re looking for! The range of diseases that can affect animals is not a fixed target. New diseases crop up more frequently than you might imagine and even the diseases we think we know about can change in the way that clinical signs present. Sneaky pathogens! So how should we organise ‘scanning surveillance’ for a range of unknown animal diseases in the 21st century?

Scanning surveillance at APHA

Since the 1970s, APHA (and predecessor organisations) has developed a comprehensive network of specialist Veterinary Investigation Centres that perform post-mortem examinations and testing on livestock at the request of vets and farmers with the intention to provide definitive diagnoses that are as accurate and reliable as possible. At one level, this provides a valuable diagnostic service that enables farmers to better manage their animals. At another level, combining lots of data points, especially as they come from a subpopulation of sick animals, provides an effective way to maximise the chances of picking up new and unusual diseases and provides evidence of changing patterns of diseases in the national livestock populations.

There are some slight disadvantages of the system. Firstly, it takes time to make a definitive diagnosis based on a post-mortem examination. It is not just the time to perform the examination but added to that there are additional diagnostic tests that are necessary to confirm a diagnosis and to interpret the results. And, secondly, the reality is that the total number of animals being examined in this way is relatively small.

What about the future?

The question we have to ask ourselves is: in this world where we are awash with data and where we have access to powerful computers and mind-bogglingly complex software, are there any other data sources that could be exploited that would enable us to get a whiff of a disease ‘signal’ sooner than is currently possible?

Useful data is being generated routinely at many points in the livestock production cycle: by farmers and producers to help manage their livestock businesses, by veterinary surgeons to record details of farm visits and treatments, by fallen stock centres, commercial diagnostic laboratories and abattoirs. If we were able to access and analyse these vast data-sets quickly and automatically, perhaps we could pick up disease-related signals in animal populations sooner than is currently possible. These alternative data sources may never be able to replace the very high quality data being generated at Veterinary Investigation Centres, and they are certainly not intended to, but they may be able to raise suspicions of a problem at an earlier stage which could subsequently be investigated in more detail.

As such, APHA’s Surveillance Intelligence Unit is currently investigating ways to collect and make the best use of these additional sources of data to provide valuable information about animal health whilst, at the same time, ensuring that personal data is not used inappropriately. Just as with the supermarket shopping example at the start of this blog, individual pieces of data considered in isolation are generally uninformative, meaningless and potentially misleading but, considered together with vast amounts of other data, it is possible to develop systems that can extract valuable meaning from the apparent chaos of large data sets.

Therefore in future, scanning surveillance for livestock diseases may not rely on a single source of information but, instead, may use multiple data sources that are analysed alongside each other to produce a more holistic view of diseases and the impacts they have on us and our economy in the animals that provide our food.

Watch this space!

Find out more

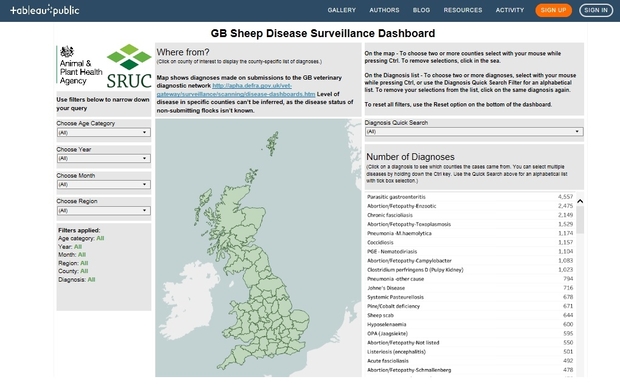

APHA publishes the results of its scanning surveillance activities through a range of reports, including the disease surveillance and emerging threats quarterly reports. In more recent years, APHA’s data has been presented as interactive plots and maps that are publicly available online so you can explore the ‘dashboards’ for sheep, cattle, poultry and pigs.

Enjoyed reading? Then why not subscribe to the APHA Science Blog

1 comment

Comment by Mark Chambers posted on

Dear Phil. No doubt this is the future and I believe some of the Scandinavian countries are doing some interesting work on syndromic surveillance of this nature. Always happy to link you up to the huge number of world-class scientists using AI at the University of Surrey. This sort of thing is right up their street/field/stream.