Ticks are particularly unpleasant creatures. They bite us, cause infestations in livestock and pets, and are a source of numerous pathogens that cause diseases such as Lyme disease, tick-borne fever and tick-borne encephalitis.

Every year on 6 July, World Zoonoses Day highlights the importance of understanding diseases that can spread between animals and humans. To mark the occasion in 2025, this blog features Ben Jones and Nick Johnson as they delve into their work identifying viruses found in ticks across the UK. Their research recently led to the discovery of a zoonotic virus, underscoring the vital role of ongoing surveillance in protecting public health.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines zoonoses as those “diseases and infections that are naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and man”. About two thirds of the diseases that affect humans are zoonoses and many of the pathogens APHA test for, fall into this category.

The TickTools project, led by APHA, was established in 2023 with a grant from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and Defra, to investigate the microbiome (all organisms present, for example, bacteria, fungi and viruses) of ticks infesting animals in the UK.

Ben Jones from the TickTools project describes the process of obtaining a tick microbiome:

The first step in the process of obtaining a tick’s microbiome is to sterilise a deceased tick with bleach to remove any bacteria, fungi or other microorganisms that may be on the outside of the tick. This could have come from the environment or from the person that collected the tick. We then use a machine that shakes a tube containing the tick, a metal bead and a cell-breaking chemical, until all that is left is a murky liquid that contains all the genetic information (DNA and RNA) that was once inside the tick. This can then be isolated from the liquid, allowing us to determine the genetic sequences of all the organisms present.

We take these genetic sequences, piece them together and compare them to a reference database to help us to identify all the different organisms that were in the tick. The majority of genetic sequences that we find usually come from the tick itself. This is useful for studying the genetics of the ticks and can help us to understand how ticks from different parts of the country are related. Aside from that, we usually see a lot of bacterial and fungal species, with the occasional virus. This approach can only match sequences back to known references within our databases and so cannot help us to find anything new.

However, the TickTools project has given us the tools to be able to identify viruses that have not been detected before. To do this, we first piece together overlapping sequences of DNA to form longer sequences called contigs. We then scan these for key patterns that are commonly found in many viruses. If we spot those patterns, we compare the sequence to known viruses to find the closest match and check if it has all the necessary genes of a complete virus. By using these approaches, we can identify potential pathogens that are carried by ticks in the UK, which can then inform approaches taken to prevent animal diseases and zoonoses.

Earlier this year, the Mammalian Virology group detected a novel virus infecting hedgehogs submitted to APHA from rehabilitation centres (Is a newly discovered virus contributing to the decline of our wild hedgehogs? – APHA Science Blog). However, the story did not end there. As a result of this investigation, large numbers of ticks and fleas infesting these animals were recorded on each animal, perhaps not a surprise to anyone who has encountered a hedgehog.

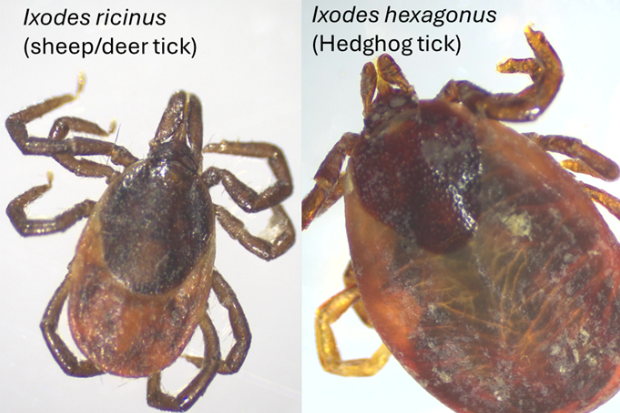

This presented an opportunity for the TickTools project to take advantage of these samples. The ticks removed from hedgehogs looked similar to the common sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus) but were all the hedgehog tick (Ixodes hexagonus). This species infests burrows, and although rarer than the common sheep tick, the UK tick surveillance scheme does receive reports of tick bites by this species and it has been reported to bite humans and domestic animals.

An initial finding from this study was the identification of Alongshan virus (ALSV): a previously undetected virus in the UK, found in the very first tick we examined and a pathogen originally detected in ticks in China. This is significant because although the TickTools project encounters many viruses associated with ticks, the vast majority do not present an immediate risk to humans or animals. Following the discovery of ALSV in China, several human cases involving fever and neurological symptoms linked to tick bites, were subsequently reported in the region. These were all attributed to ALSV infection. This triggered further studies that detected antibodies to the virus in sheep and cattle.

Our discovery of ALSV in UK ticks has been reviewed by the Human Animal Infections and Risks Surveillance group (HAIRS). The genomic sequence of the UK virus was quite distinct to those viruses found in Europe, Russia and China. So far, there is no evidence of infections in humans or animals, but this discovery provides the opportunity to prepare public and animal health bodies for the emergence of this virus and continue to raise awareness about the dangers of infectious diseases associated with tick bites.

2 comments

Comment by Rudolf Reichel posted on

Have you looked at the presence of C burnetii, the cause of Q fever? As far as I know it has not yet been confirmed in ticks in GB

Comment by Heather O'Sullivan posted on

We have seen evidence of a Coxiella sp. in the hedgehog tick that had ALSV. We have not yet completed the analysis necessary to confirm whether it is C. burneti or another species of Coxiella endosymbiont.