Continuing our celebrating votes for women series, Flavie Vial, a statistician in the National Wildlife Management Centre, explores the achievements over the last 100 years of the many women scientists within APHA and its predecessors. This blog looks at the early years (1930-1949).

Last month was an exciting time for many of us, kicking off with the third International Day of Women and Girls in Science (which my team, the National Wildlife Management Centre team blogged about).

This was followed a few days later by a blog marking 100 years since (some) women obtained the right to vote, aged over 30 and all men over 21. Following on from this, we continue in a series of blogs to acknowledge women scientists at APHA.

At a time when gender inequality both in and out of the professional sphere is very topical, taking a look back over the last 100 years felt like a positive way to gauge how far along that road we have travelled as an agency. It also serves to promote discussions about how we can continue to work together to tackle equality and diversity in the workplace.

Throughout these posts I will share the achievements of some of the notable women scientists within APHA over the last 100 years. My view is that these scientists and their achievements are notable in their own right – not just because they are women!

Without further ado, let us start at the beginning…

The early years (1930-1949)

As far as I can tell the first publication from a woman scientist to come out of the Central Veterinary Laboratory (CVL) was authored by Dr Ruth Allcroft in 1935, on a rather niche topic, 'Rapid titrimetric estimation of arsenic in biological material'.

This wasn’t Ruth’s first publication either: she published in 1933 under her maiden name of Ruth Strand a paper entitled 'Studies on the lactic acid, sugar and inorganic phosphorus of the blood of ruminants' with a WM Allcroft, who would that same year become her husband!

Ruth Strand was born in Lower Hutt (New Zealand) in 1904 and graduated with a BSc in 1928 from what was then known as the University of New Zealand.

Ruth left New Zealand to settle in Aberdeen where she obtained her PhD in 1934 at the Rowett Research Institute. She likely moved from Aberdeen to join the Biochemistry Department, and her husband (who was at Rowett on a Ministry of Agriculture Research PhD Scholarship between 1930-33), at CVL sometime between 1934 and 1935.

Ruth was extremely prolific as a scientist (even by today’s standards) and published dozens of articles on mineral deficiencies, and excesses in cattle and sheep in Britain, including a paper in Nature in 1946.

In recognition of her work, she was a recipient of the Queen’s Birthday Honour and made an Officer of the British Empire in 1959. She retired from CVL in 1968 and both her and William left the UK to settle back in New Zealand.

These early years for women at CVL have to be considered in view of the greater historical context. The threat of biological warfare, led in 1939, to an urgent programme for the production of anthrax vaccine and antiserum on an unprecedented scale.

Eric Hulse (who joined the CVL in 1937), recalls in an interview published in the ‘Outlook’ staff newsletter in summer 2006:

“The beginning of the war was apparent in more ways than one. The first real sign of the war was that the lab had to employ women for the first time. [I] was given six young school leavers to train as lab technicians in the first week of the war. This presented a problem as up until now all technicians, except the chief technician, wore brown lab coats and the scientists wore white lab coats. But of course, all staff were male. [We] had to select a new colour and style of lab coat, suitable for the new lady employees. Green was the chosen colour.

“By the end of the war, the number of women had grown to around 50 in C-block alone. Of course, when this building had been designed and built, CVL only employed male laboratory staff so there had been no need to build female bathroom facilities. C-block only had one toilet and it was quickly taken over by the women. The men had to use an old outside toilet by the boiler room that had no washbasin, or run cross-legged to the main building.”

The war also had a direct impact on the type of scientific research that was carried out at CVL. T E Gibson explained:

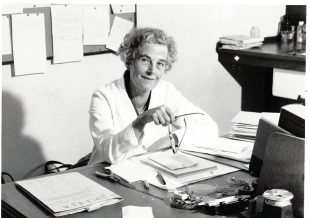

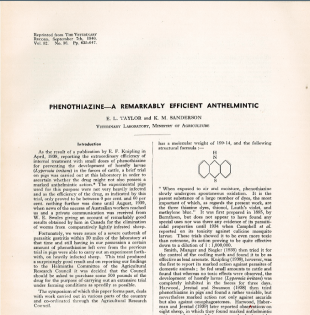

“[…] at the beginning of the war […] the laboratory had to give priority to problems concerned with food production and […] the production of various biological products required for the war effort. Following reports from the USA and Australia of the value phenothiazine as an anthelmintic, it was natural that [we] should evaluate the drug under UK conditions. In 1939, Miss Katharine Sanderson was appointed to assist in this work and a paper was published in 1940 describing the activity of the drug in sheep, goats, cattle and horses.”

Katherine Sanderson resigned in 1941, perhaps ahead of her wedding in January 1942, and nothing is known of her career after this point.

Enid Evans (née Smedley) joined the Imperial Bureau of Animal Health (a predecessor of the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI)) also based in Weybridge in January 1940, after being lured by Katherine Sanderson, who was a former colleague of hers at the Imperial Bureau of Agricultural Parasitology in St Albans, where they had shared a "precarious existence on research grants in helminthology".

At the age of 28, this was Enid’s first salaried post, earning £250 per year. My research leads me to believe that Enid may have been Canadian and graduated with a BSc (Hons.) from the University of Manitoba in 1931 with a major in parasitology, before working for a time as a demonstrator in zoology at University of Western Ontario.

Enid was involved in the production of the Index Veterinarius. Published annually from 1933, the Index Veterinarius was a complete index to publications relating to veterinary research and public health administration and education, indexing around 10,000 references each year.

It was Enid’s responsibility to check all abstracts dealing with parasitology and zoology. When Ruth Allcroft joined the staff, she had responsibility for the nutrition, physiology and chemical aspects.

Another major scientific development at the time was the increasing success of treatment of bacterial infections with the advent of organically produced antibiotics such as gramicidin, the product of gram-positive bacteria.

A vast amount of literature was being produced around this topic and Ruth Allcroft published a review in 1942 of the value of gramicidin, demonstrating its bacterial efficacy but also warning against its toxicity (Allcroft, Ruth, 1942: Antibacterial agents derived from micro-organisms with special reference to gramicidin. The Vet. Bull Vol 12, No 1, pp. 1-66)

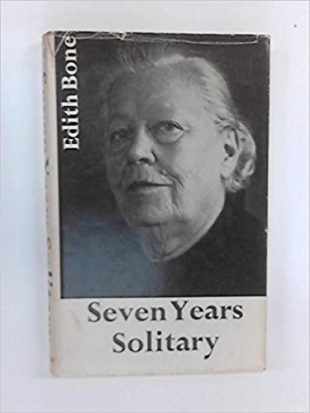

Other notable women at the Imperial Bureau of Animal Health during the war included "Valerie Robinson, a Quaker and a conscientious objector who left after the war ended […] to join the Friends Relief Service in Germany”, and a translator, Dr Edith Bone, “an elderly woman doctor of Hungarian origin and strong Communist sympathies […] who made the mistake of returning to Hungary at the end of the war, and was promptly imprisoned as a suspected British spy”.

Watch a short interview with Edith upon her release.

Enid vividly recalled the working condition during the harsh winter of 1946-47:

“Our offices were heated by wall-mounted gas fires, and on several afternoons these burned so low that we turned them off for safety. There were power cuts too […] so we sat in our winter coats and gloves, poring over proofs by candlelight, while outside the murky yellow light of midday darkened to another foggy night”.

Enid stayed at the Imperial Bureau of Animal Health until mid-1947, when she returned to St Albans to become Deputy Director of the Imperial Bureau of Agricultural Parasitology.

Researching the lives of these fascinating women has been equal part frustrating, as a result of scarce archives (although I am both surprised and thankful for some of the rare finds on the internet), and equal part fascinating/humbling.

My sincere thanks go to Joanne Butler and Steven Maloney from the APHA Records and Enquiries team, Cathy O’Sullivan from Defra Library, and the Special Collection Centre at the University of Aberdeen for their enthusiastic help in tracking down the documents and testimonies I used when writing this post. My sincere apologies must also go to the women scientists I will have invariably missed during my research for this and future posts.

Read more...

Sunday 11 February was the third International Day of Women and Girls in Science. Read our APHA science blog to hear from more of our scientists who came together to celebrate women in science.

Read our second blog, Celebrating the centenary of votes for women, where our scientists at the National Wildlife Management Centre (NWMC) tell us about their achievements during their careers, many of which would have been unthinkable 100 years ago.

You can also read the Civil Service blog to find out about the many different ways the Civil Service is celebrating the centenary of women's suffrage in 2018, including their Suffrage Flag Relay and their blog 100 years, 100 women to showcase women in public life over the last 100 years.

Don't miss future science blogs in the 'Celebrating Votes for Women' series - follow APHA on Twitter and sign up to email alerts.

Recent Comments