Chris Nichols interviews David Everest of the Pathology Department at APHA Weybridge about how work in the bio-imaging unit led him and colleagues to undertake a long-term study on adenovirus in UK captive red squirrel breeding programmes.

This work ultimately illustrates the importance of comprehensive viral health checks when reintroducing red squirrels and can be extrapolated to reintroduction programmes of many much loved British wildlife.

How did you become involved in red squirrel surveillance?

The interest started in 2006 when I was offered a posting to the then electron microscopy (now bio-imaging unit), where viral diagnostic detection in domestic and wildlife species was part of the work programme. It provided an opening to a field that I thought could be developed to benefit the agency and its surveillance activities.

We were already seeing numerous detections of squirrelpox disease among red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris), increasing the demise of this native species, which in conservation terms is a biodiversity action plan species. The eurasian red squirrel is an example of a native mammalian species being extirpated by an invasive alien species, the eastern grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), both through competition and squirrelpox disease, caused by the squirrelpox virus, for which it acts as an immune reservoir, but is invariably fatal to the native species.

Where does adenovirus come into the picture?

Finding squirrelpox cases was expected, but we were also seeing sporadic cases of adenovirus (ADV) being detected in Cumbria, from 2006. This was a virus only previously seen in the species once before in 1997, following a re-introduction project involving the trans-location of red squirrels from Cumbria to Suffolk. That set me thinking about a possible link.

A link between reintroduction projects and adenovirus?

I began researching about red squirrel conservation groups and enquiring whether they had found any dead red squirrels which might be sent for analysis under what is now the APHA Diseases of Wildlife Scheme and received several contacts which was helpful.

I was contacted by a group who were re-introducing red squirrels to Wales via captive breeding enclosures, with stock donated from other collections in England and Wales, and had recorded deaths there in 2005 and 2006. No definitive cause could be attributed, due to excessive decay to the bodies through delayed discovery, a familiar scenario in captive breeding programmes, as the squirrels are generally of a similar size and have similar pelage characteristics, so detecting clinical cases is difficult.

I contacted the International Zoo Veterinary Group (IZVG), a company who specialise in performing clinical examinations on captive species from zoological collections and was kindly provided with post mortem data to investigate.

What did the post mortem data reveal?

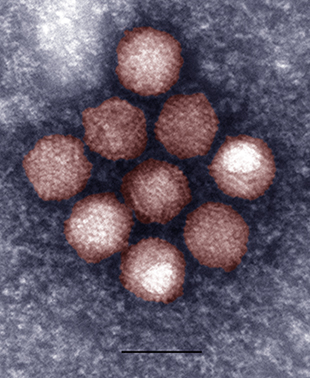

In October 2007, I was contacted by the group involved with the Welsh re-introductions about 3 recent deaths from one of their enclosures, with signs which were similar to the previous deaths. I was sent faecal material from these animals by IZVG to investigate by electron microscopy and detected ADV particles in each case, the first time ADV had been detected in captive red squirrels.

Further enquiries between ourselves, the group and IZVG provided a common link between the deaths, namely the location of the donor stock collection and the collection where some of them were quarantined.

Archive material from the 2005 and 2006 cases which was only suitable for analysis by PCR was obtained from IZVG and with help from the APHA virology department, we found that, amplified ADV DNA was detected in each case, totalling 21 animals from these 2 locations.

Did these results lead you to undertake a more long-term study on captive red squirrels?

Not directly at that time. We began to detect more sporadic cases in wild animals and had some different captive collections asking for analyses and these also led to ADV detections, in some cases involving several animals and possibly associated with movement of donor stock between collections.

Finally in 2010, with help from the UK captive red squirrel breeding scheme whose constituent collections are members of the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums and the Red Squirrel Survival Trust, a questionnaire was produced asking for information on husbandry and mortalities among collections.

The results of this were the primer for the study as they indicated a level of mortalities between collections that were going unrecorded, so vital data was being missed. We contacted these groups and recovered archived material where possible and appealed for animals to be submitted for analysis to provide study material.

Can you describe the captive red squirrel study in a bit more detail?

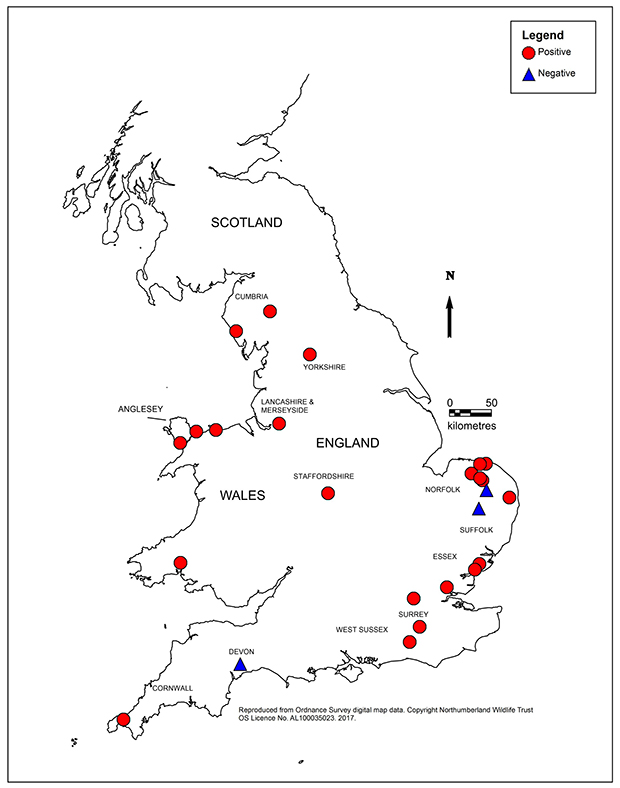

The study had received material from 181 dead red squirrels, of which 129 (71%) were suitable for clinical examination, with a range of tissues taken for analysis. These animals came from 26 English and Welsh locations, incorporating 22 permanent collections and 4 sites associated with red squirrel re-introduction programmes.

In all, we detected 92 (71%) of the 129 animals positive for ADV, either by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or PCR. This level far exceeded the figure involving wild red squirrels which we had undertaken previously, where we found 14% were positive for ADV. This reflects higher densities within captive collections and the intimate association of mothers and their kittens in contact within nest boxes.

Detections were made from 23 of the 26 locations, including all 4 sites associated with active re-introduction programmes. Inter-collection movement was associated with ADV presence at recipient collections following arrival of donor stock. But, one collection saw a number of deaths associated with ADV from home bred stock, no donor animals having been received for a number of years. This collection subsequently donated stock to 7 other study collections following the ADV outbreak and of the 7, 6 experienced ADV cases following stock receipt. Pre-movement testing was not a consideration across the study and bio-security was varied at best.

What was the ultimate study outcome?

As far as we are aware, this study is the only one of its kind in the context that it was undertaken and has shone a bright light into the world of captive breeding and trans-location and re-introduction programmes.

Forget that these are red squirrels involved, equally they may be any mammalian species, such as bank voles, dormice and pine martens. Each are iconic native species under active re-introduction programmes so the results we identified could easily be extrapolated to them. Although we are not able to recommend approaches, the study recognised that the importance of health screening and quarantine for any animal translocation, particularly for species of conservation concern should not be overlooked.

The study also concluded that standard protocols mitigating for infection spread among collections be provided, incorporating both robust quarantine and effective hygiene measures. Rodent control (wood mice) should also be undertaken until their possible role in ADV transmission to red squirrels is determined and pre-movement testing involving both TEM and PCR on faecal material as a minimum should be prioritised.

Since the study was published in October 2017, 2 further collections not known to us, one a permanent location, the other associated with a further red squirrel re-introduction programme, have been examined and both have proved positive for ADV. There are also two known captive collections in Germany with confirmed ADV outbreaks.

Our work illustrates that comprehensive viral health checks are extremely important if reintroduction programmes of many much loved British wildlife are to succeed.

The study has been published online (DOI: 10.1016/j.mambio.2017.10.003) ahead of print in the journal Mammalian Biology.

Follow APHA on Twitter and don't forget to sign up to email alerts.

2 comments

Comment by Holly Everest posted on

Well done Dad! 🙂

Comment by Angus Wear posted on

Great to see your passion and scientific approach in reaching these significant conclusions. I'm sure your recommendations will have a positive impact on the future survival of red squirrels and other species too. Well done indeed.